Growing up in a Japanese WW2 internment camp in China

- 17 August 2015

- From the section Asia

Mary Previte first had an inkling that World War Two had ended as she lay in bed, trying to fight off dysentery and the unbearable heat of a Chinese summer.

Suddenly, she heard an unusual sound: planes flying over the Japanese-run internment camp where she had been held for nearly three years.

"I jumped and looked out of the window and saw a plane flying low over the treetops and then parachutes started dropping. It was an instant cure for my diarrhoea," she said.

"People were crying, weeping, screaming, dancing, jumping up and down and waving at the sky. They were hysterical," said Mary, describing the scene at the camp when people realised what was happening.

The planes had brought US soldiers, who soon afterwards liberated Weihsien, an internment camp for 1,500 prisoners in China's Shandong Province.

Decision to stay

It was the beginning of the end of a long ordeal that had seen Mary, then just 12 years old, separated from her parents for more than five years.

Before the war, Mary had been living in China with her parents, Christian missionaries who ran a Bible school in the city of Kaifeng in Henan province.

Her mother and father worked for the China Inland Mission, one of the largest missionary organisations then operating in the country.

It had been founded by Mary's great-grandfather, James Hudson Taylor, a preacher from Barnsley, once an important coal mining town in the north of England.

The China Inland Mission, now renamed OMF International, recently held an event in Barnsley to celebrate the organisation's 150th anniversary.

When Japan first invaded China, its troops mostly left the Westerners there alone, so Mary's parents decided to stay on in Kaifeng.

"They had actually bought tickets to return to the United States, but my dad said, 'God didn't just call me to be a missionary here in good times, he called us to be here in good times and bad'," said Mary.

But as a precaution, the couple sent their four children - Kathleen, James, Mary and John - to a school for foreigners in Chefoo on China's eastern coast in Shandong.

The couple thought they would be safer there and, for a while, they were.

Japanese takeover

But that changed when Japan's attack on Pearl Harbour drew America into the war. At a stroke, Mary and her family, and many other Westerners in China, became enemy aliens.

The day after Pearl Harbour, Japanese troops marched into the Chefoo school and declared themselves in charge.

"They brought a Shinto priest to the ball field who conducted a ceremony. They came bringing pieces of paper with Japanese writing on them and glued them to tables and chairs, pianos, desks; all of it belonged to the great emperor of Japan," said Mary.

She remembers how the schoolchildren would watch the Japanese at bayonet practice. They called it "Ya" practice because that was the sound made by the soldiers as they charged towards each other.

The school had become a prison and Mary - then just nine - was a prisoner.

The young girl and her siblings were also cut off from their parents, who remained in unoccupied areas of China throughout the war.

The children stayed at Chefoo for a year, until the Japanese decided to turn it into a military base. The pupils and their teachers were transferred to a larger camp at Weihsien, set up to hold civilians from Allied countries who had been living in China.

Mary, who was then called Taylor, said she would never forget the day they were all marched out of the school.

"That was the end of Western domination of China," she said. "They had crowds of Chinese along the roadside as these white people were carrying whatever they could in their hands - no servants were helping them now - marching off to concentration camp."

'Rat-catching contests'

Life in the new camp was more difficult than in Chefoo. The Japanese guards were strict, although they would occasionally show kindness.

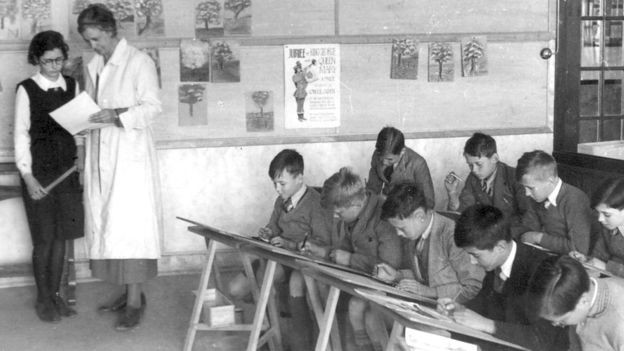

Mary praised Chefoo School's teachers who turned problems into games.

If there were too many rats, the teachers would set the children the task of catching them. It was the same for flies and bedbugs. There were small prizes for the winners.

Mary describes the teachers' actions as "beautiful triumphs".

"Our teachers set up a comforting, predicable set of rituals and traditions. Do you know how safe that makes children feel?"

But the children could not be shielded from all the horrors of an internment camp.

There was little medicine and some people died, including the British prisoner and former Olympic athlete Eric Liddell, or "Jesus in running shoes," as Mary describes him.

And then towards the end food became scarce.

The doctors among the prisoners asked anyone trading in black market eggs to save the shells, which were baked, crushed and then fed to the calcium-deficient children.

"It was vile. It tasted like you were eating sand," remembers Mary, who is now 82.

The prisoners knew little of the war going on outside the camp so when it ended it came suddenly and without warning.

When the US soldiers arrived at the gates of the camp, they were carried inside on the inmates' bony shoulders. They were treated as heroes.

A few weeks later Mary and her siblings were flown to Xi'an in central China and had a tearful reunion with their parents.

The family decided to return to the United States and Mary worked in education before being elected to the New Jersey state assembly for the Democrats.

Later in life, in the 1990s, she decided to try to find each of the six US soldiers who had liberated Weihsien camp.

She criss-crossed the country visiting each one, or their families in the cases where the soldiers had died. "I wanted to see them face-to-face to say 'thank you'," said Mary, who spent two years tracking them down.

The only person Mary was not able to contact was a seventh soldier on that mission, the Chinese translator who had accompanied the US paratroopers.

Then a few months ago a Chinese student studying in the US saw an article about Mary and realised that the missing translator, Eddie Wang, was his grandfather.

He got in touch with Mary, who was then finally able to have an emotional telephone call with the 90-year-old Mr Wang in China.

Weihsien was liberated 70 years ago, and Mary was just 12 at the time, but the friends she made there and the experiences she endured have stayed with her for a lifetime.